5 Reasons Universities are Renovating Student Housing

As universities strive to offer student housing that aligns with the expectations of contemporary students, many are faced with the need to renovate or replace existing residence halls to provide a modern array of amenities. COVID-19 further complicated these capital project decisions, constricting budgets for private and public institutions. In the following, Clark Nexsen’s Student Life practice leader, Peter Aranyi, discusses the benefits of renovation and why it offers particular value to campuses nationwide.

As universities strive to offer student housing that aligns with the expectations of contemporary students, many are faced with the need to renovate or replace existing residence halls to provide a modern array of amenities. COVID-19 further complicated these capital project decisions, constricting budgets for private and public institutions. In the following, Clark Nexsen’s Student Life practice leader, Peter Aranyi, discusses the benefits of renovation and why it offers particular value to campuses nationwide.

w

Much of the student housing in need of renovation today was built for the “boomer” generation of the 1950s and 1960s. Facility design for this generation was more pragmatic than anything, with a large portion of new buildings constructed simply to accommodate the large influx of students. These buildings were generally made with concrete or steel frame structures and built to maximize space. Today, although they have held up physically, the systems, finishes, and furnishings have reached the end of their life cycle.

These renovations can range widely from ‘systems renovations’ (addressing the mechanical, electrical, telecommunication, and even structural systems) to more comprehensive approaches that enhance bathrooms, lobbies, and community areas and upgrade finishes. Comprehensive renovation can fully transform the residential setting for students and reinforce the campus community, delivering on institutional goals for student life.

New construction offers considerable freedom and value, but renovation can deliver meaningful results with cost and schedule efficiencies.

In addition to its positive impact on the student experience, renovation offers several key benefits in areas including cost, schedule, sustainability, historic preservation, and campus compatibility.

Reducing Cost and Schedule

Perhaps one the greatest advantages of renovation is its ability to reduce costs and shorten project timelines. Assuming the building structure is sound, the cost of a comprehensive renovation is generally 70 to 75% the cost of new construction, because the site preparation, structure, and sometimes building envelope can be retained. For example, at Penn State University, we simultaneously worked on a comprehensive renovation of South Halls (left) and the new construction of Chace Hall (right).

The South Halls renovation was a complete transformation of this complex, which houses more than 1,000 members of the university’s 32 sororities. The addition of limestone-clad building extensions with dormers served the dual purposes of enhancing the façade and disguising piping and ductwork distribution. New covered porches enrich the buildings’ character, define entrances, and enhance social interaction.

South Halls consisted of four steel frame, 254-bed residence halls built in 1958, while Chace Hall is a new steel frame residence hall. Both projects were completed at the same time, designed by Clark Nexsen and constructed by Barton Malow Company, utilizing the same subcontractors. Overall, the new construction project cost 32% more per square foot and 27% more per bed than the comprehensive renovation project.

Perhaps one the greatest advantages of renovation is its ability to reduce costs and shorten project timelines. Assuming the building structure is sound, the cost of a comprehensive renovation is generally 70 to 75% the cost of new construction, because the site preparation, structure, and sometimes building envelope can be retained.

In addition to the “hard” cost of demolition, site preparation, and new building construction, time is another reason universities choose renovation over new construction. Depending on the level of abatement or demolition required, site preparation can take anywhere from three to six months. The construction of a new structure and building envelope can also take three to six months, depending on the choice of systems. Tacking on as much as a year or more to the construction schedule adds the “soft” but very real cost of lost revenue (xxx beds x $x,xxx cost per bed) and construction cost escalation (3% to 7% per year, depending on the region of the country). In a nutshell, renovation gets beds online faster without sacrificing the student experience.

Adding & Enhancing Amenities

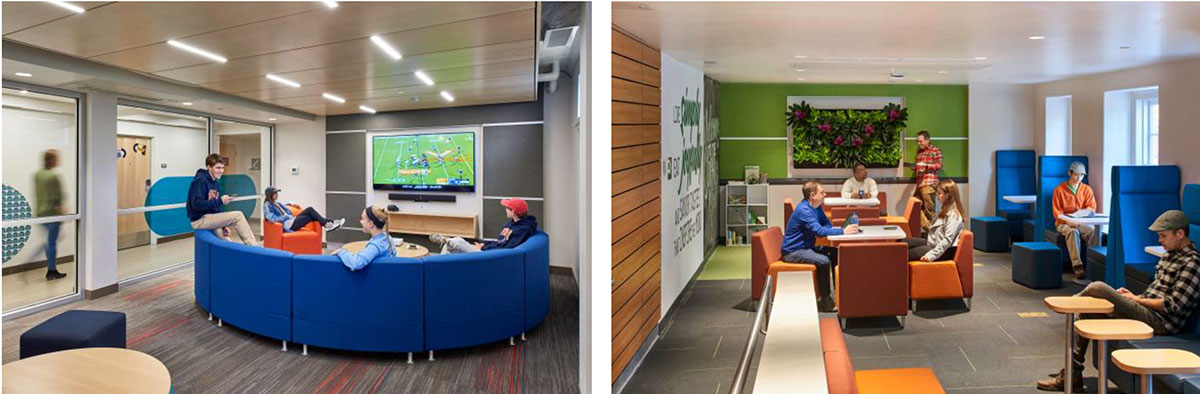

Most older residence halls lack the amenities that appeal to today’s students. If those amenities do exist, their design, finishes, and technology is typically in need of an update. Built in the 1950s to serve freshmen students, Bonnycastle Hall is part of the McCormick Road Houses complex at the University of Virginia. Prior to their renovation, the buildings lacked many of the amenities and creature comforts found in newer residence halls on UVA’s campus. New interior finishes and an emphasis on transparency and daylighting create a contemporary aesthetic and make the space more attractive to students.

The commons spaces on the ground floor of UVA’s Bonnycastle Hall now feature floor-to-ceiling glass storefront and colorful, modern furnishings. This openness and transparency in shared spaces appeals to students and encourages socialization and group study.

Transforming “The Castle,” a dining and social space, significantly increased exterior gathering space around the restaurant area. By opening the exterior walls and introducing a lantern-like addition on the corner, the Castle and its surrounding outdoor plaza have become a vibrant hub of activity with increased connectivity to campus.

Improving Sustainability

It’s been said that the most sustainable building is the one you don’t build—which is another plus in the renovation column. By renovating, you are saving energy in a variety of ways: the embodied energy in the original structure, the energy used to demolish it, and new energy and materials to rebuild from scratch. The Bonnycastle Hall renovation, for example, reused 90% of the existing structure and building envelope, in addition to adding insulation, new windows, and energy efficient systems.

By renovating, you are saving energy in a variety of ways: the embodied energy in the original structure, the energy used to demolish it, and new energy and materials to rebuild from scratch.

The result is a LEED Silver certified building that has driven energy consumption down by nearly 50% compared to a baseline renovation. New plumbing fixtures also provide a significant reduction in potable water usage.

Supporting Campus Compatibility

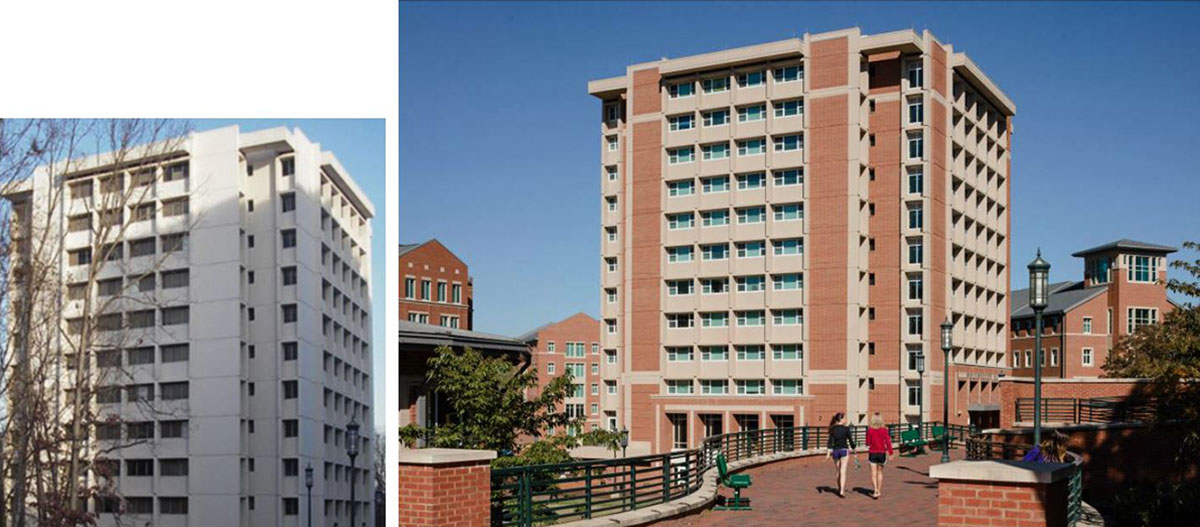

As relatively young campuses like the University of North Carolina at Charlotte mature and develop campus standards in architecture, residence halls with sound concrete structure and significant bed count in the “too big to fail” category are receiving exterior upgrades. These upgrades aim to reinforce campus identity by creating a more consistent aesthetic, whether that aesthetic is traditional or more modern.

To better align with the plethora of other brick buildings on campus, the “Brutalist” concrete façade of UNC Charlotte’s Holshouser Residence Hall was detailed in brick and cast stone. Additionally, entrance canopies and patios were added to refine the scale of the buildings and provide outdoor community spaces for students to congregate.

Preserving Historic Buildings

In contrast to the necessary renovation or replacement of post-World War II buildings found on campuses across the country, many pre-war buildings have significant historic value and architectural merit. Unlike the post-war buildings, which were built for economy and often had very low floor-to-floor heights, the pre-war buildings had both significant architectural character and higher floor-to-floor dimensions, allowing for more graceful integration of new mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and fire protection systems.

Duke University’s West Campus is a great example of some of the best Collegiate Gothic campus architecture in the country. The renovation of the Craven and Crowell Quads sought to transform the interior student experience while preserving the iconic exterior architecture.

Whether the goal is to provide new amenities or repurpose an entire facility, there is no one-size-fits-all formula that should guide universities to renovate versus build new. New construction offers considerable freedom and value, but renovation can deliver meaningful results with cost and schedule efficiencies. For every building under consideration for renovation, a feasibility study is instrumental in defining the opportunities and constraints of renovation and will help determine the best course of action.

Whether the goal is to provide new amenities or repurpose an entire facility, there is no one-size-fits-all formula that should guide universities to renovate versus build new. New construction offers considerable freedom and value, but renovation can deliver meaningful results with cost and schedule efficiencies. For every building under consideration for renovation, a feasibility study is instrumental in defining the opportunities and constraints of renovation and will help determine the best course of action.

Lead image of a community space in Clark Nexsen’s renovations to Edens Quad Residence Hall at Duke University.

Peter Aranyi, AIA, leads Clark Nexsen’s Student Life practice and works with college and university clients to design dynamic student life communities. To learn more about how renovation can add value on your campus or to speak with Peter, please call 704.377.8800 or email paranyi@clarknexsen.com.